Prologue

On January 12, 2008, my brother, Thomas Pyle Reid, Colonel, USMC (Retired), was interred with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. After training at Parris Island, South Carolina, he served as an enlisted Marine in several Pacific battles, had been wounded, returned to his unit immediately after having been evacuated to a navy hospital ship, and continued to serve until the end of the war in the Pacific. He was eligible to receive the Purple Heart. After the war he entered Johns Hopkins University, continuing service in the Marine Corps Reserve. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned for officer training at Quantico Marine Base. Upon completion, he was sent to Korea as a platoon leader during the early days of the Korean War. He was awarded the Silver Star for bravery in combat with the enemy and received a second Purple Heart for wounds received in combat. He returned to the U.S. and completed a doctoral degree in jurisprudence, continuing to serve in the Marine Corps Reserve until retirement. His interment at

Arlington National Cemetery honored his long and honorable career of service to his country.

My wife, Dee, and I had planned to attend the interment ceremony with our daughter, Stephanie, and son, Jeffrey, traveling from San Diego, California, where we were spending the Christmas holidays. Unfortunately, Dee and I became ill with the flu and could not travel. At the ceremony, Stephanie and Jeffrey became reacquainted with their aunt, Connie, their cousins, and their families. In discussing their Uncle Tom, it became apparent that there was little written record of the years he and I had spent growing up. It was suggested that I was the only remaining source for information about these early years and that it would be helpful to both families for me to provide such a record. I agreed to start the project and continue as long as possible. It should be noted that I had begun a personal account of those early years several years ago, but had lost it when I changed computers. I had tried desperately without success to recover the manuscript and had finally given up trying to recreate the pages I had lost. Subsequent events have again encouraged me to undertake the task of describing what it was like

growing up with my brother Tom.

The Early Years with My Brother Tom

I have been fortunate during my life to be able to record photographically in my mind places, events, and facts that might otherwise have escaped my memory. Thus, my earliest memory was of living in a home in Narbrook Park, Narberth, Pennsylvania. As expected, most of my brother’s and my waking hours were spent with our mother, Mary Elizabeth Polk Pyle Reid. Our father, Alban Elwell Reid Sr., worked as a factory manager for the A.H. Reid Creamery and Dairy Supply Manufacturing Co. located in West Philadelphia. His father, Alban Hooke Reid, had invented the cream separator as well as other equipment related to the dairy industry and had created a very successful manufacturing business. He was by reputation a stern, self-contained man with a number of idiosyncrasies, among them the determination to walk daily to, and from, his apartment on Chestnut Street to the factory on Sixty-ninth Street, a distance of thirty blocks. It was said he could be identified easily because he always allowed his handkerchief to hang from his back pocket to dry.

As a factory manager, our father was expected to open the factory in the morning and shut it down at night, six-and-a-half days a week. Tom and I were still in bed when he left for work in the morning and usually fast asleep when he returned home at night. (I have a vague recollection of our mother being frightened at least once in the night when she thought someone was peeking at us through a window. Most of our contact with our father came on the weekends when we were held accountable for things, both good and bad, that we had done during the week. One session stands out in my memory. Tom and I disliked a little neighbor girl who insisted on following us around and taunting us. One day, when we felt that she had pestered us enough, we decided to teach her a lesson. We held her and loaded her bloomers with gravel from the road. She went screaming home and her mother came to tell our mother what we had done. I don’t know why two young boys would have decided to do what we did. We were barely out of diapers when it happened. When our father heard of our transgression, we were shut

up in a closet for what seems now like several days, living on bread and water. Dad had recently returned from the war in Europe where he had served as a lieutenant in the Transportation Corps, riding a motorcycle to transmit dispatches from point to point. (He had prepared for his commission by attending a summer training camp in upstate New York while he was enrolled as a student at the Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania.) It probably seemed appropriate to him to punish his sons the way they would have been punished had they been in the army, thus solitary confinement and bread and water. Fortunately, while he was gone during the day, our

mother saw to it that we received proper nourishment.

I do remember during our time at Narberth being taken with Tom to a movie theatre where we heard Al Jolson sing “Sonny Boy” in the film, “The Jazz Singer.” The theatre also presented a full-color kaleidoscope projected on the screen, probably a precursor to Technicolor years later. “The Jazz Singer” was the first motion picture to have sound. The Jolson connection became significant years later when he traveled to Trinidad on a USO tour and I, as a newspaper journalist in the army, did promotional releases on his travels within the command. U.S. newspapers picked up the releases, and his career, which had been all but dead, was suddenly revitalized. Shortly after his visit, Hollywood

released the biographical film, “The Jolson Story.”

Grandfather Reid had worked on the family farm between Coatesville and Downingtown, Pennsylvania, after the death of his father, James Reid. In an early census, he was listed as a wooden-bucket maker. He was reputed to have spent much time sitting under a tree, thinking. Rather later in life he had come upon the idea of creating a machine that would separate cream from milk instead of waiting while cream naturally rose to the top of a bottle or pan. He had also invented and installed a device that cooled the milk as it was transported in a coil immersed in water that was pumped from a well. I remember seeing this rig when visiting the Reid homestead, which stood on a hill overlooking the Brandywine Creek (of Revolutionary War battle fame). Tom and I swam in a deep pool on the Brandywine. A later account by our cousin, James Reid Alburger, told that Grandfather Reid was fascinated by the idea of man flying, and built a glider that our dad was reported to have flown off the hill above the Brandywine. When the Wright brothers flew their powered aircraft at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina,

Grandfather Reid was reported to have visited them there soon afterward.

We also visited our mother’s parents at 101 West Twenty-ninth Street in Baltimore, Maryland, where we became acquainted with uncles, aunts, cousins, and Pearl, a black servant, who kept food on the table and generally kept the house running. I remember our mother telling us that Pearl had taken care of her when she was a baby. Mary Turner Polk Pyle, our grandmother, was a very austere person who seems to me, in retrospect, to have only tolerated the male grandchildren, of whom Tom and I were the principals. Uncle Whitey and Aunt Alberta Roberts and cousin Mary Polk Roberts, resided with Grandmother and Grandfather Pyle in the large, four-story, attached brick house on West Twenty-ninth Street. Whitey, who had played “professional” football with the Canton, Ohio team, (one of the original non-college football teams in the country), was vice-president of the Borden Company franchise for eastern Maryland and Delaware. I remember dessert for dinner each night was an ample serving of one of Borden’s many different flavors of ice cream. Aunt Alberta, I thought, took a distinct

dislike to me and seemed not to be pleased when Tom and I played too boisterously with Mary Polk. She was interested in the family lineage and I learned later that she was instrumental in searching out the connection with Charles Polk, who was listed as a patriot of the War of Independence and thus enabled her to join the Daughters of the American Revolution, where she became a regent. She also traced the lineage to Richard and Gilbert De Clare, farther and son, who forced King John to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, which entitled her to become a Dame of the Magna Carta.

Fanny Stalfort was our mother’s eldest sister, whom I remember as being a very sweet and generous person. Her husband, Edwin, was a chemist who had developed and manufactured several different kinds of waxes, one of which was White Sail, a liquid wax sold through a national grocery chain. Aunt Fanny died in a horrible automobile accident in Delaware. Their daughter, Mary Selma Stalfort, an older cousin, was about twelve at the time and did not get involved with Tom, Mary Polk, and me. Uncle Charles was a very short and jovial man who always seemed to relate to the children, though he and Aunt Mary Pyle had no children of their own. Bud, as he was known by his sisters,

had taken over management of the McDowell Pyle Confectionary Company, which grandfather Pyle had created from his beginnings as a candy sales representative in Delaware. He had lived as a boarder in great grandmother Polk’s house and had married our grandmother, Mary Turner Polk when she was just seventeen. Our mother’s younger sister, Theodora Polk Pyle, was married to Henry William “Bill”

Morgan, Jr., who was involved in real estate in Washington, D.C. I recall very little of their three children except that they were much younger than Tom and I were. Of course, I also very vaguely remember our great-grandmother, Sarah Fawcett Polk, who spent much of her time in her bedroom upstairs. I was only three when she died. We had no contact with the Baltimore relatives for years after we eventually left for Florida. I have a dim memory of Grandfather Pyle’s funeral. The Pyle-Roberts household seemed to be very much what would today be called a matriarchal residence.

My next recollection was attending Grandfather Reid’s funeral at our Aunt Josephine’s home in Lower Merion, Pennsylvania. I have a visual picture of him lying in his casket while family and friends talked. I was about four at the time and Tom was three. Since Grandfather Thomas Jefferson Pyle, our mother’s father, died within the same time period, and our grandmother, Mary Elwell Reid, had expired in 1903 while our dad was still a boy, Tom and I were left with only one grandparent, Mary Turner Polk Pyle.

Shortly after grandfather Reid‘s death, we departed Narberth and went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Dad was studying finance and investments at Babson Institute. We had a great time playing in the great rooms of the Institute and in the office of Roger Babson. He was at that time an icon of the financial world, teaching economics and advising on investments. We learned much later that although Grandfather Reid had left the factory to our dad, and much of his property and wealth to our Aunt Josephine, the will had been challenged so that now the factory and real estate went to Aunt Josephine and her husband, Elmer Alburger. Much of the cash went to our dad, which was presumably why he was studying investments at Babson. (Josephine and Elmer soon after sold the factory, and thus ended the potential for continuity of the Reid inventive genius which could have been embodied in our father who, we understood, held several dairy equipment patents in his own right).

After Dad completed his studies at Babson, I recall a period when we visited a wealthy man in Spring Lake, New Jersey. He had a sumptuous home facing the ocean, with house servants and a massive Pierce-Arrow car in which we traveled to the beach. Many years later, we learned that Harry Merritt was maintaining his lifestyle in part by investing Dad’s money in his schemes, which eventually went south. Dad later spent

several years in Chicago pursuing a suit against Merritt, which resulted in Merritt going to prison for a period of time. When he was released, he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where, amazingly, Dad took us to visit him.

One of Dad’s investments resulting from his studies at Babson was an orange grove located outside of Tampa, Florida. We packed up and left Narberth to settle in a very beautiful home in Temple Terrace, a suburb of Tampa. On the way to Florida, we were driving down a dusty road when we came upon a black woman lying in a ditch beside the road. It appeared that she had been struck with a piece of wood that was lying next to her. We slowed as our parents tried to decide what to do. Apparently, they decided that there was nothing they could do, so we continued down the road. After a while, we came across a man who was walking rapidly away from where the woman had been. Again, it appeared that there was nothing we could do, so we continued on our way to Florida. That scene was recorded in my mind some eighty years ago, yet the image is as vivid in my mind today as though it were just yesterday.

Almost as soon as we arrived in Florida there was a freeze, which killed off most of the trees in the orange groves. That ended our dad‘s Florida odyssey, for he soon became involved in another type of enterprise in the Midwest. Tom and I were enrolled in a school near our house to which we walked every day. Unfortunately, we had to pass a house where there was what seemed to us to be a gigantic chow dog. I can remember his black tongue as he barked at us when we walked past. I forever after have had a loathing of that type of animal. We were always afraid he would break his chain and attack us.

I can’t remember how Tom fared at school, but I recall that I had my first crush on a little blonde girl named Sally. We had a small white spitz dog that went berserk one day and tried to climb up the fireplace chimney. During his rampage, he turned from white to black. I don’t remember his departing, but suddenly there was no longer a dog in our lives. One of my more vivid memories was of the “tomato standoff,” where our dad insisted that I finish the sliced tomatoes on my plate before I could leave the dinner table. I sat for what seemed like hours before I was finally allowed to go to bed. I’m certain that dad won the contest, but it left me with a lifelong aversion to sliced tomatoes. I remember that both Tom and I developed scarlet fever, which at that time was considered to be a fairly serious illness. We spent some time being cared for in our beds. Those were the same beds where punishment was meted out for misbehavior. I can remember some rather sharp slaps on my rear from my father’s belt. He also managed to put some dents in Mother’s sterling silver Stieff hairbrush. (Years later that

brush was willed to my wife, Dee, and it still had the dents that had been placed there from contact with my bottom. It also disappeared one day when we were packing for a move in California. We believe it went to a cleaning woman who had a questionable background and a thirst for liquor. Somehow our liquor bottles remained at the same level while the contents of the bottles were clearly becoming more diluted.)

I recall Dad leaving on a trip to Detroit, Michigan, probably as a result of his failed orange grove investment. He was reportedly working with an insurance firm there. During his absence, we had a housekeeper and a handyman/chauffeur who looked after the family. It was during a visit home from Detroit that our dad and mother had a violent disagreement. I have a vivid memory of my mother standing on the couch in her stocking feet and flailing wildly at our dad while he attempted to block her blows. He disappeared back to Detroit shortly after this event, and it was the last time, at ages four and five, my brother and I were ever to see the two of them together. Tom and I became more and more dependent on our housekeeper and the handyman. After some time, our mother decided to visit her mother in Baltimore, leaving us in our home with the housekeeper. It was during her absence that our housekeeper decided to drive to her daughter’s house in our family car. Apparently, the daughter and her husband were brewing beer in their bathtub. When it came time to return home, they presented several

bottles of beer to their mother. Tom and I were loaded into the back seat of the car. Since I was older, I was given responsibility for protecting the bottles by holding them between my legs. The car started up and we backed out of the driveway and across the street, where we hit the curb at a sharp clip. The bottles came together between my legs and broke. Beer spewed over me, mixed with blood from cuts on my legs. We eventually got home, stopped the bleeding, and went to bed. To this day, I still have the beer-bottle scars on my legs. I don’t recall being taken to a doctor at the time, which might have required explaining to him about my cuts and why the clothes of a five-year-old were saturated with beer.

The next vivid memory was of our dad arriving at the house and telling us to pack our clothes since he was taking us back to Detroit with him the next day. Years later we learned that he had heard that our mother was returning from Baltimore on the advice of her mother and an attorney, and planned to reestablish herself in the Tampa home. I also learned that Dad had packed up and sent all of the rugs and furniture to storage. I believe the rugs and a desk showed up later in our lives, but many of the other possessions eventually were lost or sold off for non-payment of storage charges. (Within the past few years, I was contacted by a bookseller in upstate New York who had a Reid family bible that he thought I might be interested in purchasing. I forwarded $150 and found that I had actually regained possession of the authentic Reid bible, with hand-written notes on the births and deaths of several generations of the Reid family.) The trip to Detroit was uneventful and our stay there provides only vague memories of attendance at a summer day camp in the city park. At the end of summer, Dad drove us

to the place where we were to spend the next three-and-a-half years of our lives. It was during this time that Tom and I learned to depend on each other, since we had no contact with our mother and limited contact with our dad, though he wrote letters to us, and came to take us on trips during vacation times.

Four Years at Pembroke Country Day and Todd School

Our new and only home was Pembroke Country Day School, located on State Line Road, Kansas City, on the Kansas side of the Kansas-Missouri border. Tom and I shared a dormitory room with two beds, dressers, and desks. Our days were highly regimented, with meals on time in the school dining hall, classes well organized, and physical activities encouraged. I remember studying French in first grade. In third grade, our class published a magazine for which I wrote a poem and rendered a drawing of the gates at the entrance to the school grounds for the magazine cover. I remember sports activities as a vital part of our educational program. We were taught to play tennis. We

had our own football and baseball teams. I somehow became a pitcher for the third-grade team; we played against other school teams. We traveled to an Indian school in Kansas where we played against their teams. The schools were created to remove Indian youngsters from the reservations and indoctrinate them in American culture. In the spring we had relays where we competed in track-and-field events. I believe I took several medals, but Dad was most pleased when I took a medal in the high jump because he had been a star high jumper in high school in Philadelphia.

Mrs. Kennedy was our housemother as well as a teacher. She kept us from feeling very alone, helped us write letters to Dad, and saw that we went to church on Sundays. She monitored the evening study hall and controlled the behavior of the older students when they became unruly. I remember only a few of the students at Pembroke from those times. One boy was fascinating because he had a crystal radio set which he used to tune in to broadcasts from a station in Iowa. It was amazing that he could use a simple little wire to pull voices from the air. By contrast, our dad had a massive box in the back of his car that required a battery to operate. He had to park the car and string out an

antenna in order to have reception. Particularly outstanding among the students were the Rockne boys, Bill and Knute, Jr., who attended Pembroke. Their father was the coach of the Notre Dame football team. At one point, he brought Frank Carrillo and the other members of the famed Four Horsemen, who motivated the Notre Dame football team to visit the campus. Knute, Jr., though small in size, was a very competitive athlete and an important member of all of Pembroke’s teams. Bill was bigger but did not seem to be interested in sports. As I recall, he liked to smoke cigarettes out back of the garage. Much of the joy went out of their lives the day they were called from our luncheon in the dining hall to be told that their father had died in a plane crash. Coach Rockne’s fame lived on in film and legend and became an inspiration for future Notre Dame teams. I later learned that Knute, Jr. went on to play football for a college team in Florida, but never achieved the kind of success that might have been expected of him had his father lived.

During the Christmas holiday of our first year at Pembroke, our dad picked us up at school and told us that we were going to drive to Florida. He drove a very powerful Auburn convertible with what was called a rumble seat in the back. We took off driving from Kansas toward Florida on roads, many of which were unpaved. When we found paved roads, they were narrow strips of concrete. We arrived in Tampa in time to witness the annual holiday pirate parade. Returning from Florida, we drove to Washington, D.C., and then to Baltimore, where we later learned that our dad had contacted our mother to attempt a reconciliation. Her version, many years later, was that he had simply wanted

her to visit him in his hotel room. She was apparently enjoying her single life in the city and had no intention of rejoining him.

We left Baltimore and headed back to school. During the trip, Tom and I thought it was great to ride in the rumble seat. Since we were traveling through the Midwest during the Christmas holidays, it was extremely cold. One night we encountered a muddy pothole on the gravel road. The car dropped into the hole and we were stuck. Dad tried to rock the car out of the hole but finally gave up and looked for help. There was a light on at a farmhouse just off the road and the farmer seemed ready to help us, but it required hitching up his team of horses. Apparently, there was some haggling over the price of the farmer’s help, but finally, we were out of the hole and on our way. Our dad

commented that the pothole was filled with corn cobs which, when covered with mud, made it impossible for the car to gain traction. He thought that the farmer had probably loaded the corncobs into the hole to generate income from his towing enterprise.

By the time Tom and I returned to Pembroke, both of us had developed serious cold infections. We were signed in to the school infirmary where we stayed for some time. In those days it was not unusual for an infection to move into the ear and then into the mastoid bone behind the ear. The common treatment for this condition was to surgically remove the infected bone. At least one student at Pembroke had had this surgery with a resultant deep scar behind the ear. As I recall, the ear infection was painful, and I know now that there were no drugs available then to treat the infection effectively. Fortunately, both Tom and I recovered without the need for surgery, though I have retained a ringing in my ears throughout my life, a condition called tinnitus.

After our recovery, Tom and I were taken to a courtroom to testify about our mother having left us to visit her mother in Baltimore. We learned later that our Dad had filed for divorce from our mother. We learned much later from our mother that she had not been notified of the proceedings. Dad knew she was living with her mother in Baltimore, but had failed to have documents sent to her; thus she had not had the opportunity to present her side of the case. I remember how strange it felt to be children whoseparents had divorced. Divorce was unusual in those days and Tom and I felt somehow responsible for our family’s break up.

During the summer when school was out, Dad arranged for us to attend a summer camp on Lake Superior in northern Michigan. Camp Sosowagami was located at the confluence of the Yellow Dog River and Lake Superior so that we could skinny dip in the lake at daybreak and have swimming and canoeing classes in the river during the day. Unfortunately, the lake water was ice cold, and the river, though warmer, was shared with leeches that attached themselves to our bodies and had to be removed when we came ashore. One of the activities fostered by the camp involved boxing matches. I remember being paired with a boy about my size who somehow managed to keep his gloves in my face during the entire match. I have no memory of how he looked because I don’t believe I was ever able to see him because of his gloves. I was never very much interested in either participating in or watching boxing matches or fights after that experience. I believe that Tom had a more successful time in his match. The camp had a very active riding program. Each day we reported to the stables and were given our mount for the day. Access to the trail required crossing a stream. One of the horses regularly insisted on stopping midstream, lying down, and rolling over. The horse’s rider regularly wound up getting a bath in the middle of the stream. As luck would have it, being one of the younger campers and last to arrive at the stables on my first outing, I drew the horse that intended to give me a bath, and he gave me a bath. I found in subsequent outings that it was possible to convince the horse to cross the stream without stopping if you were willing to show him who was boss. However, I tried my utmost to draw one of the other horses that did not like to roll in the stream.

Tom and I returned for several camp sessions until the fall of what would be my fourth grade, when Dad informed us that we were transferring to Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois. He had moved from Detroit to Chicago, where he was involved in court proceedings against Harry Merritt, and he felt it would be better to have us closer to him. Todd School was a totally different experience for us. We still lived in

dormitories, but our rooms were located in large old mansions and were more comfortable than the rooms at Pembroke. Classrooms were spread around the campus and classes seemed more informal than at Pembroke. I still studied French as well as the other regular courses, but there seemed to be more emphasis on the arts and music and less on sports. I had been recruited to play the clarinet in the band at Pembroke. At Todd, I played in an orchestra-type organization instead of a band. Tom was given a fluegelhorn to play. I continued to play my clarinet until I had to pawn it for food money in Philadelphia in 1940. I don’t know what happened to Tom‘s horn. I played intramural basketball at Todd, but was not very good. I had somehow left my competitive spirit at Pembroke. I was pleased that we did have stables and a riding program at Todd. We also had an indoor swimming pool to carry on the swimming we had learned at summer camp. Because we were close to Chicago, and because the school had a kind of trailer/limousine, we were transported in groups to the city for various kinds of cultural

events. I remember seeing my first rodeo there, as well as plays and musicals.

Todd School and its headmaster, Roger Hill, we’re particularly proud of its theatrical productions. The school had a theatre and a workshop where sets were made and rehearsals held. One of the sets had been created for a production of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” The production had been conceived and directed by a student who had graduated the year before. The student was Orson Welles, who was sixteen when he graduated and had left for a painting tour in Ireland. He had procured a horse-drawn wagon and was making his way around the island, painting as he went. Weekly, he wrote letters to Roger Hill, who had become a father figure for him after the death of his

own father. These letters were regularly read to the assembled students by Roger Hill during lunch. In them, Orson described his experiences as he made his way through the Irish countryside. When he arrived in Dublin, one of the first places he visited was the Gate Theatre, which was in the midst of a period of brilliant productions based on the works of William Butler Yeats, Sean O’Casey, and other playwrights and poets of the time. Welles, by his own account, introduced himself as a visiting producer and director who would be pleased to work with the theatre group as a director. He was given the opportunity to participate in productions as a set builder and painter. Eventually, he was

given a role in one of the productions where he portrayed a mature English nobleman, even though he was still in his early teens. During his time at the Gate Theatre, he met a number of actors and actresses, including Barry Fitzgerald and others, whom he later brought to the United States to work with him when he became director of the WPA Theatre in New York City, which evolved into the Mercury Theatre on stage and radio.

For some reason, Tom and I were to remain at Todd School for just one term before returning to Pembroke. Perhaps it was because our dad had completed his involvement in Chicago and had become involved as a partner in the American Union Life Insurance Company in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Sometime before he left Chicago, I remember that we visited him in his room at the Blackstone Hotel which, we learned later, had been host to ten presidents during its glory days. What was most memorable was his insistence that we start every morning with a glass of unsweetened lemon juice. It was supposed to be good for our systems but was hard to down. After his move to Tulsa, we visited his

office at one point, but had no further contact with American Union Life. Our last semester at Pembroke was unremarkable in my memory. Perhaps it was during that time that I played tennis and won my medals at the spring relays.

Three Years As Iowa Farm Boys

While we were at school in Kansas and Illinois, Dad had introduced us to the McWilliams women, who were the children of his aunt, Maria Reid, and her husband, William McWilliams, originally from Pennsylvania. The family had settled in Des Moines, Iowa, where they lived in the 1930s. Blanche McWilliams, a maiden lady like her sister, Mame had worked all her life in the U.S. Post Office in Des Moines. She was an

asthmatic who slept on an enclosed porch in the coldest of weather. Mame maintained the home for her parents and her sisters. A third sister had been a buyer for the major department store in Des Moines and had traveled to Europe extensively. Martha, the fourth sister, was married to Charles Campbell, who farmed 160 acres of rich cornfields near Grimes, Iowa, twelve miles southwest of Des Moines. She was a talented pianist who taught piano to students in and around Des Moines. Charlie was an equally talented fiddler who was in demand to play for platform dances (explain what these are) held around the countryside during the summer. It became routine for us to spend holidays in Des Moines with Blanche and Mame. On one of our visits, Dad decided that I needed to have several of my teeth pulled. We went to a dentist who anesthetized me and proceeded to remove all of my wisdom teeth in one sitting. Even today, I recall the trauma of the rubber mask over my face and the horrible odor of the gas. During the night, I hemorrhaged profusely on my pillow. I apparently survived but I can’t remember

visiting another dentist for a number of years.

It was during our last Christmas at Pembroke, when we visited Des Moines, that we discussed the possibility of spending our summer vacation on the Campbell farm rather than returning to Camp Sosowagami. Tom and I were very excited at the challenge of a totally new kind of experience. We were encouraged by the enthusiasm with which Martha and Charlie considered the prospect of our spending the summer with them. I believe that Tom and I returned by train to Pembroke by ourselves after that visit. I should probably note that we considered Des Moines a marvelous place to visit since we were allowed to go downtown alone to movie theatres where, on the same day, we could watch double features at one theatre and then go to another theatre for two more movies before heading for home. I remember especially Elizabeth Bergner in the film depicting the love affair of the Austrian prince and his young fiancée, who supposedly committed suicide while visiting a hunting lodge in the Austrian mountains.

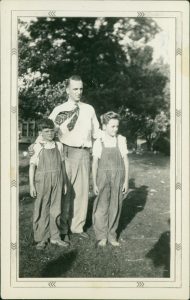

Tom and I were excited as we anticipated spending the summer on a real farm, seeing live farm animals, and riding horseback. (We eventually discovered that farm horses were workhorses that were not ridden). Dad drove us from Pembroke to the Campbell farm, and suddenly we were farm boys. We were given our first pair of overalls. Although we didn’t know it at the time, this was the uniform we were to wear for the next three years. As I recall, we wore our riding boots from school and camp under our overalls rather than the high-laced dress shoes that we had worn at school. Our school blazers and grey flannel slacks went into storage for the duration. Our first initiation to

farm life was getting up at first light to a large breakfast of pancakes and eggs. We watched as Charlie hitched up a team of horses to a cultivator and headed for the fields where the corn was just beginning to show up in rows. He spent the entire day plowing up and down one row of corn after another. He stopped only for noontime dinner and, as the sun went down, he turned to other chores: feeding horses, cows, hogs, and milking the cows, of which there were at least a dozen. Tom and I quickly learned from Martha how to feed the chickens and gather eggs, and those chores soon became our responsibility. In time, we would learn to throw down hay for the horses and cows, mix slop for the hogs, and even milk the cows.

In a short time, we were charged with herding the cows up from pasture to the farmyard. We found it great fun to go barefoot, though accidentally stepping into one of the pies the cows left behind as we followed them up from pasture produced a strange sensation. Tom and I slept in a feather bed under the eaves of the farmhouse. Iowa summers were hot and our bedroom was hot! Opening windows did not provide much comfort and it did allow mosquitoes to harass us at night. Since both Martha and Charlie were frequently away from the house during the day, Tom and I had many opportunities to experiment. I recall our challenge matches to jump out of the second-story window.

One day, Tom decided to try some of Charlie’s chewing tobacco. Martha discovered bits and pieces of tobacco in the bedclothes. Rather than physical punishment that our dad used to correct our errant ways, Martha and Charlie delivered a lecture on the unhealthy impact of chewing tobacco on growing boys. Sometime later, Tom and I discovered the joys of smoking cigarettes. By this time our mother had located us through our Aunt Josephine, who knew and visited with the McWilliams and had started sending small amounts of money to the Campbell’s for us. We found a slightly older Seibert boy who lived a mile down the road who shared one of his cigarettes with us. In due time, we

used some of the money to have him buy a pack of cigarettes for us. Cigarettes sold then for about twelve cents a pack, about the same price as a gallon of regular gas. A pack could last us for at least two weeks. Another of our escapades involved siphoning off a Mason jar of wine from the cellar, loading the wine with sugar, drinking most of it, and then climbing the windmill to prove we could. It was scary climbing onto the platform with the windmill blades whirring just above our heads. We discovered that climbing down was more frightening than climbing up, but we managed to get down before the Campbell’s returned. Of course, some of these events occurred at a later time during our stay at the farm.

During that first summer, Tom and I learned many things about farm life. We learned not to turn our backs on the resident bull, whether in the pasture or the barnyard. Cows could also be annoyingly protective of their calves. Hogs were not to be trusted even when you were trying to feed them, and farm horses were different from the horses we had ridden at camp and school. We helped as best we could during haying season when the hay was mowed, hauled to the barnyard, and hoisted to the hayloft where it would dry and then be thrown down to feed the horses and cows during the coming winter. We learned about cooperation among the farm families. When the grain was ready for harvesting, a huge threshing combine, which was owned cooperatively by local farm families, was rolled out of the Campbell barn where it had been garaged, and taken to the farm where the first grain was to be threshed. Early in the morning, the local farmers assembled with their wagons to bring in the sheaths from the fields. A tractor was hooked up to the threshing machine with a long belt and the threshing process commenced. Sheaths were fed into the machine, grain was collected in a wagon, and the chaff was stacked for later use in the barn. Water bottles were delivered to the fields by boys on horseback. Meanwhile, the ladies and children had spent the morning preparing the noon meal, which was served on tables set out in the farmyard. There were enormous quantities of all kinds of farm-raised food–meat, potatoes, corn, vegetables, different kinds of salads, bread, cold tea, and many desserts. The men and boys ate first, then returned to the fields; then the women and children took their turns. When the harvest was completed at the first farm, the threshing machine was moved to the next farm where the process was repeated. When the harvest had been completed, the machine was wheeled back into the Campbell barn to remain until the next year’s harvest.

By the time the grain had been harvested, the corn had been cultivated three times and was tall enough to continue growing on its own. It was time to stop and relax a little. It was also time to visit the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines. As I recall, we drove to the fair on three consecutive days to visit those exhibits that were of interest to Charlie and Martha. There was also time for Tom and me to view some of the competitions that we saw for the first time. Farm boys wrestled greased pigs, or tried to climb a greased pole; boys and girls showed the animals they had raised during the previous months for judging and winning ribbons. There were daily horse races as well as appearances on stage by different musical groups. Tom and I had seen things in a few short months that probably none of our former schoolmates had seen or would ever see while at Pembroke or Todd. We were tired and happy as we rode back to the farm at the end of each day.

August marked the end of the summer for us. The corn would not be ready for shucking until later in the fall. We had not heard from our dad about returning to Pembroke. We began to talk with Martha and Charlie about school. We wondered if we could stay on the farm and go to school there. There was a one-room schoolhouse across the road from our house. We thought it would be great if we could simply walk down the road each day, go to school, and then walk home in the afternoon. Martha and Charlie found that we could not attend the local school because we were in a different district. Instead, we would have to attend Johnston Consolidated School at Johnston Center three miles

down the road toward Des Moines. The first mile from the farm in any direction was a gravel road. After that, there was a two-mile stretch of concrete paved road to the school. When there was still no word from Dad about returning to Pembroke, where classes didn’t start until mid-September, we asked Martha and Charlie if we could enroll at Johnston. They said yes, and we went off to school on the yellow school bus that picked us up in front of the house. Tom was enrolled in fourth grade and I was promoted from fifth grade to sixth grade. On the first day of school, I was introduced to the class as a new student from a school in Kansas. For whatever reason, one of my classmates decided to challenge me to a fight during the first recess. I don’t remember the outcome, but it probably wasn’t any better than my experience in the boxing match at Camp Sosowagami. After a few days, the novelty of the new boys from way out of town probably wore off. I don’t ever remember having felt the sense of belonging that I had felt during my years at Pembroke. And as a scrawny ten-year-old in a sixth-grade class, with rough and tumble farm boys who really belonged in sixth grade, I never again got involved in athletics. But we did take pride in the success of our girls’ basketball team, which earned the right to play in the state tournament in Des Moines each year. It was the major event of the year when we loaded on school buses and went into town to cheer on our team. I don’t believe we ever won the state championship; we were a very small school without the talent to overcome the sheer numbers available to the competing urban high schools.

Tom and I were well into our first several weeks of school when Dad showed up ready to take us back to Pembroke. There were some serious discussions about whether it would be right for us to stay on the farm. It was finally decided that we could stay on a trial basis, since we were already in school and seemed to want to continue. Dad eventually left and we settled in to become real farm boys for at least the first year. Though he argued vigorously for our return to Pembroke, it is probable that he was somewhat relieved at not having to pay our tuition there since, as we later learned, these were not the best years for him financially. The stock market had crashed and we eventually found out that he had an army footlocker of worthless stocks and bonds.

The first winter at the farm was a real test for us. At Pembroke and Todd, we had lived in heated dormitories with all the amenities expected in a private school. We had warm showers, heated classrooms, and, in the case of Todd, a heated swimming pool. Our activities there were directed toward recreation. At the farm, our activities were directed toward surviving! Although the farmhouse was spacious, with a number of different rooms, we lived in two rooms heated in winter by an iron cook stove in the kitchen and by a pot-bellied stove in the living room. There was no air conditioning or electricity. The toilet facility was a two-hole outhouse where pages of a Sears catalog served as toilet

paper. The back of the outhouse faced to the north, so that winter winds had a chilling effect on bodily functions, especially when it snowed. We did our homework by lamplight (kerosene) at the kitchen table. Martha was a hard taskmaster, insisting that all homework be done before we retired to bed at about eight o’clock. At night we slept in a feather bed in an unheated upstairs room. The nights were extremely cold and,

once in bed, we stayed until morning. In the morning we descended to the kitchen where Charlie would have lighted a fire in the cookstove for heat and for Martha to cook breakfast. Breakfast was a hearty meal with oatmeal, pancakes, and meat, usually sausage or fried scrapple, a solid blend of hog jowls and cornmeal. In time Tom and I would dress for out-of-doors and accompany Charlie to the barn where he would

undertake the morning chores of milking the cows. When we had learned the technique of sitting on a three-legged stool and squeezing milk into the bucket held between our legs, we were given the opportunity, and later, the responsibility, to milk several of the cows each morning before school. More often than not, we would miss the bucket and squirt the milk onto our overalls. The milk would dry in the warmth of the classrooms later at school and after several days would turn sour giving us our own aura, which was often matched by the aura of other boys in class who also did the milking at home before they arrived at school.

By early spring, we had settled into a daily routine. There was much to do around the farm from the time we arose, usually before daylight, and when the school bus stopped at the front gate to take us to school. We had to mix food for the hogs and scatter grain for the chickens. The horses and the cows seemed to survive on one feeding per day in the afternoon. In the morning during summer, Tom and I would repair to the garden with buckets and shovel to harvest potatoes for the noon meal-dinner, as it was known in the country. The four of us would consume half of a two-and-a-half-gallon bucket of boiled potatoes in one sitting. We would mash them on our plate with a fork and slather them with butter. When other vegetables were ready for harvest, they would be added to the noon menu. We ate watermelons and cantaloupes right off the vine. There were fruit trees of various kinds, and berry bushes and strawberries. We didn’t realize it until later, but while we were enjoying a surfeit of good food, other people across the country were struggling to feed themselves and their children during the Great Depression.

During the three years, we lived on the farm, we had all the chicken we could eat. Charlie taught us how to kill and clean a rooster by wringing its neck. Dipping the bird in boiling water loosened the feathers for plucking, but getting out all the pinfeathers was a problem. (Hens were kept alive for egg production; part of our daily chores called for collecting freshly laid eggs from the hen houses.) We ate a lot of chickens and eggs. Surplus eggs were cleaned and packed for transport to a market in Des Moines where they were bartered for staples such as flour, sugar, and coffee at the rate of about six cents per dozen. Hard cash was never in abundance during our stay at the farm. I remember Martha telling us that taxes on the farm were about $100 per year. Mortgage payments, when paid, were for interest-only with payment on the principal waived until times were better.

Occasionally, young steers would be hauled to the stockyard in Des Moines where, if customers were buying that day, healthy young steers would bring about four cents per pound. If the stockyard were not buying, we would turn around and return to the farm. The same was true for hogs. I remember one day when Charlie hitched the horses to a hay wagon and loaded several hogs for the twelve-mile trip to the stockyard.

Apparently, he was unable to hire someone to truck the animals to market. The trip was long, tedious, noisy, and uncomfortable. The wagon had ironclad wheels that responded to every crack and crevice in the road. Travel was slow and we arrived at the stockyard just as they were closing for the day. We turned around and headed back to the farm with our cargo intact. The price paid that day was two cents per pound, but they weren’t buying because they had all the pork they needed, or perhaps they didn’t have any money left to buy our load.

We collected milk that we did not use and placed it in cooling pans in the cellar where cream would rise to the top while the remaining milk would form clobber. We would skim the cream off the pan and place it in a container; the clobber was used for cooking. The cream would be left at the gate for regular pick up by a dairy truck. As I recall, that was one of the few sources of cash income we had at the time. One year, the farmers became enraged at the price being paid them for milk. In protest, they established a roadblock on the highway leading to Des Moines. They stopped any truck hauling milk and dumped the milk in the ditch alongside the road. Tom and I didn’t exactly understand what was happening as we drove past the roadblock, but we heard the men talking about how unfairly they were being treated. Cousin Charlie was a severe critic of the incumbent administration in Washington, and when Dad finally had a battery-operated radio installed at the farm, Charlie spent hours listening to the news broadcasts. He was particularly angry about the farm bills, which limited the acres which could be planted in specific crops, and required that litters of pigs be limited so as not to glut the market. We butchered hogs frequently to conform to the law and had an almost constant source of pork for breakfast and dinner.

In talking about cash income, I failed to mention that Martha was a well-respected piano teacher, who had a number of students in the area whose parents paid for their children’s weekly lessons. Martha tried to teach Tom and me to play the piano, without much success. She was a good teacher, but we were not very good students. I couldn’t seem to get my hands to operate individually. Years later, I realized what a wonderful opportunity I missed. If only I had tried harder, with my love of music and especially jazz, I might have been a George Shearing or better yet a Teddy Powell.

Weather was always a concern for Iowa farmers. In the spring, it either rained too early or too much or not enough. In the summer, rain at the wrong time could ruin a corn or wheat crop, or a hay harvest. Rain at harvest time could wipe out a whole year’s crop. Early frosts could kill plants just as they were ready to be picked. A period of drought as corn plants were emerging from the ground could mean little or no feed for the animals during the coming winter. Windstorms in summer could also kill crops. Tom and I learned concern about the weather not just as it related to our comfort, but also as it affected our survival. Weather also affected our mobility. The road from the highway to the farm, though graveled, could become flooded and filled with potholes. Floodwater blocked the highway to school almost every year during the spring thaw. Blizzards were also a cause for concern. I remember one winter when the snow drifted above the tops of the telephone poles on the road just below the house. The school bus couldn’t get through to pick us up. I think we tried to walk the mile to the highway but gave up almost as soon as we started. One thing was certain: Whatever the weather, there were chores to be done, animals to feed, and tasks to be performed to stay warm, dry, and fed.

Following our first experience as observers of the thrashing season, Tom and I put in a bid to deliver drinking water to the harvesters in the fields for the coming summer. We assumed that we would spend the summer on the farm again rather than going back to camp. Two things happened-somehow, we got the contract, and we also got to stay on the farm. The bad part happened when the harvest season rolled around and we realized that we didn’t have horses to carry us and the water jugs from the pump to the fields where the harvesters were working. We wound up hitching rides, with our wet, burlap-wrapped, one-gallon jugs, on wagons going to and from the fields. Once in the

fields, we had to carry our jugs from one wagon to the next until they were empty, then hitch rides back to the pumps. After a number of trips each day, we probably wished we had gone to summer camp, but we stayed with our project until the harvest ended.

Though out of touch with our mother, we did receive gifts from her through Aunt Josephine, usually small amounts of money, although she did send us roller skates one spring. The only surface on which we could skate was the highway one mile down the dirt road toward Johnston Center. Soon after we received the skates, we decided that we would skate to school. Of course, we had to carry the skates for a mile on the dirt road to get to the concrete highway. Once on the highway, things went well and we arrived at school almost on time. There were virtually no cars on the highway en route to or returning from, school. Having had one successful trip, we decided to do it again and again. The only problem was that the concrete was coarse and the skate wheels were not designed for extended travel on such a surface. After just a few trips, we were running on the rims of our skate wheels. Thus ended that experience! We had a somewhat similar experience when our mother sent us ice skates for Christmas. These were the kind that clipped on your shoes and didn’t provide much support. Fortunately,

there was a small pond in a field just across the road from our house where we could try out our new toys. I don’t believe this project was any more successful than our roller skate experience since both Tom and I had trouble with our ankles. I think I had the most trouble because I couldn’t keep my skates upright. Because of the extreme cold, the ice on the pond lasted much longer than the ice skaters. I don’t remember trying my hand at skating again for many years, and then with shoe skates and a heated rink.

We used another five-dollar gift to become entrepreneurs in animal husbandry. Having been impressed with the young farmers who raised livestock to show and sell at the Iowa State Fair, we decided that we would invest our windfall to purchase an animal. Normally, young farmers would purchase a very young animal to raise for a year to be shown at the summer fair. Tom and I were offered what was suggested as a very good deal by a nearby farmer. He had a sow (female hog) who was expecting piglets very soon. The deal was that we would not only have the piglets to raise, but we would also have the sow for future generations. As I recall, she was a huge, ugly beast who loved to wallow in the mud so that, instead of looking at her natural white color, she was always a crusted brown. We found it hard to like her very well, but then she started to give birth to our piglets. Before she had finished, we had twelve beautiful, squealing little white pigs from our five-dollar investment for less than fifty cents each. We were so impressed with our successful business experience that we lost interest in the young farmer project, and besides, we couldn’t decide which of the twelve squealers we wanted to groom for the show ring. I believe we eventually sold off the pig once they had grown up. In the interim, we were kept busy feeding them. Since we were raising them on a corn farm, we didn’t have to buy feed for them, which might have cut substantially into our profit.

Another enterprise was funded by a similar gift from our mother. Tom and I decided that we wanted to get into the business of raising rabbits. We had heard that they were equally prolific, with an even shorter gestation period. We used our gift to purchase lumber, nails, and screening material. We had designed the kind of rabbit hutch we wanted to build. Cousin Charlie advised us on details but generally left us to our own

devices on the construction part. In short order, we constructed a spacious hutch with a solid wood roof, screened sides, and a screened floor which reduced cleaning problems. The pellets we collected were very useful in fertilizing the nearby garden (which also benefited from leavings collected from the chicken coops). Today, our enterprise would have been called organic farming. I don’t recall where we procured the initial pair of rabbits, but the hutch was fully populated when we finally left the farm with Dad for Philadelphia sometime later. Raising rabbits domestically for food was not as profitable as our pig business, especially during the winter when Cousin Charlie would go rabbit hunting in the cornfields and come back with as many as a dozen wild rabbits. These we would skin and fry for dinner. I remember one day when I single-handedly managed to down two whole rabbits. Tom always kept up with me. It seemed that we were always hungry and could finish off whatever was put before us. It usually required two chickens to feed the four of us.

We both learned to catch, kill, pluck, butcher, and cook the chickens we ate. I previously mentioned the way we ate potatoes in the summer. For breakfast in the winter, we could down as many as twelve or fifteen pancakes each after chores and before leaving for school. When we butchered a young hog, we had pork for breakfast, dinner, and supper. Sometimes we would finish the whole carcass in two or three weeks. What was leftover was combined with cornmeal to make scrapple, a Philadelphia, PA, staple which came west to Des Moines with Maria Reid Williams, our grandfather’s sister. It was delicious when fried. In the summer when we went to Des Moines to barter eggs for kitchen supplies, we would usually stop at the Reed’s (should this be spelled Reid’s? Is there a family connection?) ice cream store for a gallon carton of ice cream. By the time we reached home, the ice cream would be deliciously soft and because we didn’t have a refrigerator, we had to finish off the entire carton in one sitting. If it seems that we were preoccupied with food and eating then, it should be remembered that these were the days of the Great Depression, and there were many families that did not have enough food to eat. I don’t believe we were particularly conscious of the state of the economy at the time, or that Tom and I were very fortunate to be living where we were.

Tom and I had an early and thorough exposure to the procreation process. At ages nine and ten, we observed rather clinically the impregnation of cows, hogs, chickens, rabbits, and dogs, and cats, sometimes on a seasonal basis and sometimes more frequently.

We watched as the animals gained in girth and eventually gave birth to their offspring. We loved watching the baby piglets, calves, rabbits, puppies, and kittens struggle to their feet for the first time and search for their mother’s milk. We saw hens sit over eggs which we left in nests for them until the baby chicks broke their shells and struggled to escape. For them, the world was a dangerous place where chicken hawks could swoop done down and turn them into a one-bite meal. We saw the birthing and killing of both domestic and wild creatures. We were also present when young male animals were turned into neutered beasts that lived only to grow fat, and for three to five cents a pound paid to the farmer, become meat for the tables of city dwellers. The only peer we knew who had a broader exposure to the procreation process than we did was the Erickson girl, who lived on a farm a mile down the road toward Johnston Center. Her family bred and raised horses. The breeding process for horses was described to Tom and me as something different from what we saw with our animals. We were never able to receive a precise description of the process or verify its accuracy, but it did sound interesting as it was described.

The seasons rolled by and we became more immersed in farming. Tom and I both did well in school, probably because of the solid foundation for learning established at Pembroke and Todd. There was talk of preparing for admission to the University of Iowa or Iowa State University as I completed eighth grade, though that prospect was still four years away. Meanwhile, in addition to the joint harvest festivities, we attended summer platform dances where Cousin Charlie was the fiddler of choice. He had a beautiful violin which, as I remember, was made of bird’s-eye wood. He was very careful in the care of his instrument. I remember us visiting a farmhouse down the road, where a windmill was geared to generate electricity which was used to charge a series of batteries. Power from the batteries was used to light one or two bulbs at night. When the wind blew strongly enough, it produced enough electricity to heat an iron. During the winter, cousins Mart and Charlie took us to weekly Saturday-night card games which rotated among farmhouses. Halloween was one of the few times when Tom and I got together with the local farm boys to roam up and down the roads doing whatever mischief we could. It was always rumored that outhouses were a favorite target to be pushed over, but I don’t think we ever had the strength or the courage to try to dislodge one in our neighborhood. Since the houses in our “neighborhood” were at least a quarter to a full mile apart, we were limited in how much we could do or undo in the time

we were allowed out.

For two weeks in late summer each year, life became different for us. That was when the Iowa National Guard held its summer training session at Camp Dodge, a few miles west of Johnston Center where we went to school. (Camp Dodge was where the Women’s Army Corps trained for service during World War II.) Among the units which assembled for training was a cavalry troop. It was natural for the troop to fan out across the surrounding farms to carry on maneuvers, both in daylight and at night. At least once during the two-week session, the troop would ride down our road. In daylight, it was an awesome spectacle for Tom and me. Having ridden horses both at camp and at Todd School, we were very impressed with the animals and their riders. When they rode out at night, it was an entirely different matter. We would hear the troop pass and then shortly we would hear the chickens start to panic. Cousin Charlie probably understood what was happening and approached the henhouses very cautiously, giving the raiders the opportunity to remount their horses and leave with their harvest of chickens. We lost some chickens but thought the soldiers better deserved to have fresh chicken on their dinner tables than the foxes that also stole into the hen houses on occasion, and made off with a fat hen or rooster. The foxes did more damage than the soldiers because more chickens died of fright from sensing foxes in the area.

It was probably during our third summer on the farm that we were driven to a cottage at Clear Lake, Iowa, for a two-week vacation. We were joined there by our dad and a woman whom we eventually came to know as our stepmother, Violet Hawkins. Most of our time there was spent out on the lake in a rowboat. There were undoubtedly other vacationers at the lake since I still have photographs of Tom and me with two girls in a rowboat. The other departure from summertime routines was when our dad took us to Chicago for the World’s Fair. We saw many new technological developments and visited exhibits provided by many foreign nations. Perhaps it was the year of awakening, but I remember that Tom and I were hurried past the carnival area where Sally Rand was out front with her fans, urging spectators to buy tickets for her performance.

The arrival of fall, our third at the farm, saw us indoctrinated into the process of harvesting the corn crop. We had learned how to eat as many as a dozen ears of field corn at a time during the summer when the corn was tender and sweet. As the corn matured in the early fall, usually after the first frost, we went into the fields with a horse-drawn wagon and began the harvest. Wearing cotton mittens which cousin Mart had

sewn, over what in later years would have been called a church key ( beer-can opener), we would reach up for an ear of corn, strip its husk and toss the stripped ear up into the wagon. Thus, each ear of corn on sixty or seventy acres of cornfields would have to be individually husked. We stayed in the field until the wagon was loaded, usually as darkness fell, when we would return to the barnyard where the corn later would be offloaded into a silo. What the rats and mice didn’t eat during the winter was fed to the farm animals. Since the price of a bushel of corn was not worth the cost of gasoline or the effort to haul the corn to market, where it might or might not be purchased, farmers

found it cheaper to burn the ears of corn than to buy coal for their stoves.

From an Iowa Farm to the City of Brotherly Love

As suggested earlier, if we had stayed on the farm, we might have found our way to attend one of the Iowa universities. Though farm life was hard and the monetary rewards at the time were limited by the weather and the economy, farm life was a good life, working and living among good people. Tom and I anticipated that we would continue living on the farm, and would have preferred to stay on the farm rather than going back to Pembroke or Todd. Unfortunately, neither option was to be available to us. Our dad arrived one day and told us to pack our possessions because we were leaving with him and our stepmother for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where we were going to live. The suddenness of this change in our lives came as a great shock to us and to Cousins Mart and Charlie. We had not anticipated such a change and were given no choice in the matter. The decision had been made by our dad and we would leave at once. Thus, at ages eleven and twelve we began the fourth and most challenging phase of our young lives-life in a bustling Eastern city with a new stepmother and a father

whom we knew only from occasional visits.

Though I have a vivid recollection of so many things from our early years, the transition from Iowa farm to urban Pennsylvania remains a blur. Somehow we arrived at a large house in Radnor, Pennsylvania, where we were to stay for a short while. The home was located adjacent to the Villanova University campus. It was very spacious and much more sumptuous than what we had been used to in Iowa. Sam and Lila Cummings, our host and hostess, were very kind and considerate and seemed to understand the difficulty Tom and I were having in adjusting to the total change which was taking place in our lives. Within days of our arrival, our dad and Violet (Vi to us) were married. We hadn’t realized that they had not been married when they came for us. From letters which I received after our mother’s death, I learned that she and our Aunt Josephine and Blanche McWilliams had been corresponding for some time before our dad had picked us up in Iowa. Apparently, our mother had decided to apply for visitation rights based on our dad’s having left us with the Campbells for three years with only occasional visits. His sudden decision to reclaim us may have been his reaction to that threat. The Iowa cousins were very disturbed at his behavior, especially since he had failed to make payments to them as promised during our stay. They had indicated that they were willing to continue caring for us indefinitely even without reimbursement. They had met Violet and had thought she was very young (twenty-nine years) and didn’t know what she was getting involved with. They also expressed disapproval of her relationship with our dad prior to their marriage. Added to these issues was the fact that he was having serious financial problems, and had asked Aunt Josephine and Uncle Elmer for a loan to help him get started in the Philadelphia area. The request was denied with resultant bitterness on both sides. The wedding took place at the Cummings home. Though they had been friends of the Alburgers, they became confidants and counselors to our dad and had advised him to ask for the loan from Aunt Josephine and Uncle Elmer. The outcome was a broken friendship. A small number of relatives attended the wedding, including Cousin Anna Kite, who was the only member of Grandmother Florence Jardin Kite Reid’s side of the family whom Tom and I ever met.

Violet was a very sweet person who did her best to make us feel comfortable in our new situation. And we did our best to understand an arrangement which we had not experienced since leaving Florida. Within weeks, our dad had found a large house in Wayne, Pennsylvania, which was rented with the intent of operating what today would be called a bed-and-breakfast inn, but at the time was probably better defined as a tourist home. We set about getting ready to open, though the house was in disrepair and needed much work to make it habitable for its intended purpose. Tom and I were given the task of mowing the rather large lawn. (We had developed reasonable skill in this type of project on the farm in Iowa, where the yard we mowed was equally large.) We were registered for school in Radnor. I was to go into ninth grade while Tom would enter seventh. For some reason, we would never enter school in Radnor. The tourist home project collapsed and we moved into a house in West Philadelphia owned by Mary O’Brien, who had been our grandfather’s housekeeper and had raised our dad from the time he was nine years old.

Mary O’Brien was a family fixture who had been born in Ireland and had arrived in the U.S. when she was seventeen. She had been employed by Grandfather Reid until his death when she took over the management of Aunt Josephine’s house in Lower Merion. It is ironic that years later she would provide a home for the man–and his family–whom she had taken care of as a boy. It is doubly ironic that she was maintaining her home by continuing to work as a housekeeper for a family in suburban Philadelphia. Already present in her home as a renter, was our cousin, James Reid Alburger. He had taken a job as a chemist with RCA after graduating from Swarthmore College and was commuting daily to Camden, New Jersey. On her days off, usually Thursdays, Mary O’Brien would come to Philadelphia to take care of her house. I don’t believe she ever came into town just to relax and enjoy her home. It was a typical West Philadelphia, two-story row house with a front porch that faced a tree-lined street. At the back of the house was a small fenced yard that opened to a utility alley. I don’t recall where our dad parked his car since there was no garage in the back yard.

It is strange that I have such limited memory of our first days in West Philadelphia. I assume that our dad had a job and went to work. I believe that Violet also worked, but it wasn’t until later that we learned that she became very successful in the banking industry, working her way up to bank officer (treasurer) when they relocated to Florida. After so much emphasis on food and eating on the farm in Iowa, the only memory I have of our meals in Philadelphia is that we nearly always had applesauce at dinnertime. Our meals were very simple–meat, starch, and a vegetable followed by a dessert. One entrée that I remember as being new, different, and very good, was a rolled, stuffed flank steak.

Tom and I were enrolled in an urban junior high school which was a multi-story building with an enclosed, roof-top playground where we had physical education classes and played during recesses. I can’t recall any classes where the teachers or the subject matter were particularly outstanding. I did play clarinet in an instrumental music class. I don’t remember If Tom continued playing his fluegelhorn. Several things were quite different from Johnston Consolidated School in Iowa. One was that this was the first time in our lives that we actually associated with students who were different from us– different races, different religions. We attended classes for the first time with black students. Another was the size of the classes, with sometimes as many as twenty-five or thirty students to a class. There was little opportunity for a one-on-one relationship with the teacher. Also, I don’t remember having the kind of homework assignments we were given in Iowa, where cousin Mart insisted that we not only complete our assigned projects but that we do extra work above and beyond what was required. I don’t recall

either our dad or Violet working with us on our assignments. His approach seemed to be to ask us each night if we had done our homework. At one point, because I was twelve, I was able to join a Boy Scout troop as a Tenderfoot. We had weekly meetings which eventually culminated in a campout, where we learned to cook skewered pieces of beef on an open fire. I don’t know why, but I never advanced beyond being a Tenderfoot. We had very little contact with other children, although I remember being invited to a birthday party for a girl who lived down the street from us. That was my first experience at playing “Spin the Bottle,” an underwhelming experience in my memory.

It is interesting in retrospect that Tom and I never established friendships that involved visits by other children to our home, either during the years in Philadelphia or later when we were together briefly in Florida. If we socialized at all, it was outside our home. One of our “social” activities was getting together with a group of boys and roaming the streets of Philadelphia on Friday nights. We would run up on the front porches of the row houses, collect the available milk bottles, and launch them into the street with the crash and scattering of glass, then run away as fast as we could with whoops of laughter. Fortunately, the police were involved in tracking and solving more serious crimes than we were perpetrating, and thus we were never caught. We did have one other activity which was familiar to us, that of attending weekly movies. Where the movies we had attended in Des Moines had been intended for adults, in Philadelphia we attended the Saturday matinees which always included cartoons and serials, sometimes westerns or Buck Rogers in the Twenty-first Century, or sometimes both. Admission was a dime. We usually went with a gang, probably the same ones with whom we had launched the milk bottle barrage the night before. It was not unusual to visit the local drugstore to buy candy for the show. Occasionally there was a little shoplifting done by a boy who hadn’t brought money for candy, or who thought it smart to get away with something without paying for it. Tom and I were fortunate in moving away from that neighborhood before we had a chance to find out what happens to boys who behaved the way we and our friends did. Life had definitely changed for us, as we were immersed in what became the fourth phase of our young lives. We were no longer spoiled boarding-school kids or hard-working farm boys. We were back to our original state of living as part of a family, although we had a new and unfamiliar stepmother

rather than a birth mother whom we hadn’t seen for nearly eight years. I am certain that Vi felt the same kind of discomfort in dealing with us that Tom and I felt in dealing with her. She tried very hard to care for us. It was years later when we learned just how much she contributed to the creation of whatever home life we had during those early years of our relationship.

Our year as residents of Mary O’Brien’s home in West Philadelphia came to an end with Tom being promoted to eighth grade, and my becoming a sophomore eligible to enter senior high school. We moved to an apartment on Lancaster Avenue, a few blocks from the city limits, possibly because there had been a change in family income, or because our dad wanted to move us into an area which would offer a better environment for us– or because he wanted me to attend Lower Merion High School in the suburbs of Philadelphia instead of a crowded urban high school. He arranged to have me enroll at LMHS with the understanding that I would be an out-of-district tuition student. I was to ride to school on a bus that picked me up on City Line and took me to school and back. For whatever reason, I didn’t attend Lower Merion High School, but found myself enrolled instead at Overbrook High School, a massive, multi-story building with a massive number of students. And again, there was little opportunity for a one-on-one relationship with either teachers or fellow students. It seemed that each day I was getting further and further away from the life which, although definitely unusual, had nurtured me for my first fourteen years. For Tom the experience must have been even more wrenching because we had grown apart, since we now attended separate schools and saw each other only after school and on weekends.

Though Tom and I had never, to my knowledge, attended church, except at Pembroke and at Todd School where every Sunday morning we had marched into town for the weekly service, we suddenly became heavily involved in activities at Overbrook Presbyterian Church which was located several blocks away on City Line Avenue. We both attended Sunday school services before joining our dad and Vi for regular worship and communion in the church proper. (The Presbyterian church used grape juice rather than wine, served in tiny paper cups, for the communion.) I remember our dad quizzing us on the content of the day’s sermon when we arrived home. We were encouraged to listen carefully to the message of the sermon. I had spent many evenings at Todd School engaged in a project that I had decided to undertake for my personal growth and development. My goal was to read my way through the Bible from start to finish. I believe my project anticipated by a number of years the reading of the Bible as literature rather than as gospel, which was taught when I later attended Yale University. I somehow didn’t find the connection between what I had read and what we were being taught in Sunday school and again in church. We frequently returned to the church for the evening service. It is strange now to remember how, at the Campbell’s, we had sat in front of the battery-operated radio and listened to the popular shows of that era: Fibber McGee and Molly, Amos and Andy, and bands playing from the Trianon Ballroom in Chicago, mainly on Sunday nights.

At home in Philadelphia the radio, when it was on, was tuned primarily to newscasts. Since our dad and Vi left home early each day and did not return until early evening, Tom and I began to spend much of our time after school involved in church activities. During the week there were organized basketball games. We learned to play badminton, which was different from the tennis played at Pembroke but was quite